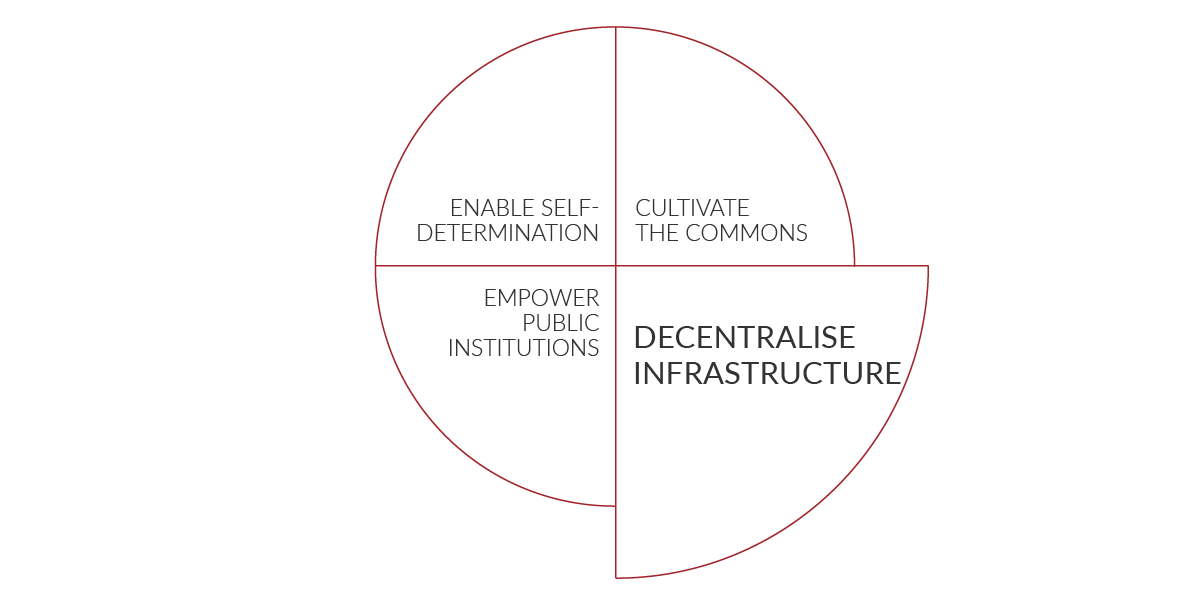

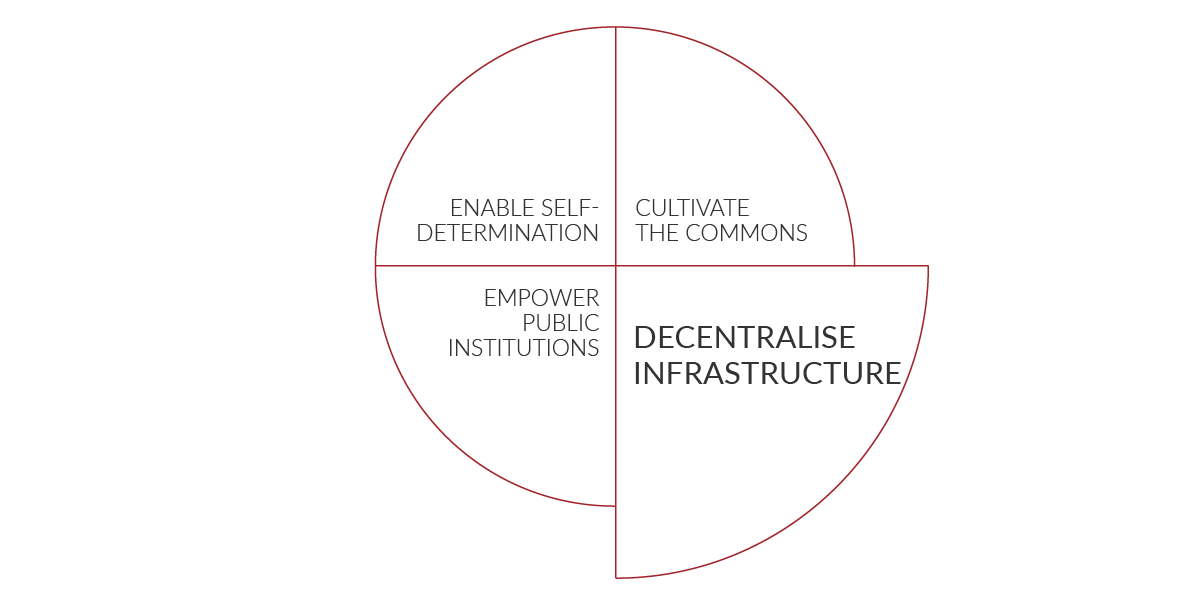

Decentralisation is the basic shift caused in the past by core network technologies, from the original packet-switching networks, through peer-to-peer content networks, to currently developed blockchain-based solutions. Decentralised infrastructure is open, distributed and shared. It is an infrastructure that can also function as a commons, and can be governed in a democratic and self-determined manner.

Infrastructure captured by global markets

In the last decade, centralised and even monopolistic services have been built on top of the decentralised infrastructure of the Internet. Since these are all very large and often non-European commercial entities, the centralisation of control over the digital networks is a form of market capture of a resource that should be treated as a universal basic service that needs to be governed as a commons. Centralisation of the Internet and the creation of online monopolies has been fueled by a range of factors that include the success of online-based advertising models, market advantages of platforms that function as two-sided markets, and a successful shift to business strategies that focus on monetisation of data instead of content. This development has led to a concentration of power in the hands of a few dominant platforms, most of which are located outside of Europe either in the US or China. As a result, much of the development of the Internet and related areas of information technology is being shaped outside of the EU.

As the Internet becomes more and more ubiquitous, with Internet-of-Things solutions diffusing in the real world, the issue of (de)centralisation concerns more than just online data and content flows. The urban environment is intertwined with the way we manage knowledge and our web-based economies. For instance, open data initiatives and policies allow people to gain an insight into city policy, and to co-create local initiatives. We need to move from the idea of ‘Smart Cities’, which mainly favour centralised technology driven by tech optimism, corporate interests and city marketing, to an ideal of ‘Collaborative Cities’, primarily driven by citizen concerns and community-based initiatives.

Similarly, the current wave of technological change and disruption related to the broad class of artificial intelligence technologies has the potential to exacerbate centralisation. Early adopters of AI solutions - which are all big tech companies - gain increased power by tapping into the capacity of centralised control through aggregation, analysis and acting upon of broad swathes of data collected on the Internet. Adverse effects of this change include increased political and commercial control of citizens, and the reduction of information and media pluralism. Centralising the management and control of transport and energy systems or housing infrastructure will make our societies less equal and sustainable.

Towards a decentralised digital space

In the last few years, Europe has attempted to counter the dominance of big technology companies by leveraging antitrust regulatory policies, which can be seen as targeting centralisation of the Internet within the boundaries of market-focused policies. Yet, decentralisation policy cannot function solely on the basis of regulation aimed at managing market competition - although it is a step in the right direction. Decentralisation is also a necessity because it can contribute to increasing democratic control. At the same time decentralization will not be the answer to all challenges, and should be regarded as being a rule that allows exceptions where it makes sense.

A decentralised approach to digital infrastructures should be applied at different levels of the technological stack of the Internet: First, decentralisation should remain a basic principle of the Internet, and should underpin projects like the European Next Generation Internet initiative. Decentralisation relates to concepts such as net neutrality and also sets clear guidelines for Internet governance. Second, decentralisation should be applied to the level of online services and should be seen as an alternative to the current model, in which data and content flows, communication and social interactions is captured by monopolistic aggregators. Decentralisation at this level entails a shift from monopolistic silos to a federated structure, in which commercial entities are regulated in how they may share data, thus breaking their monopolies. Decentralisation also means ensuring real control of users’ own data either at the individual or collective (for example municipal) level. In this way, efforts to break data monopolies also support self-determination of citizens and societies.

An effort to decentralise the digital infrastructure must provide more room for public institutions, and abstain from traditional approaches to solving societal challenges built on top-down control. We see public institutions as important drivers of a decentralised network of actors, who cooperate on solving "missions"— societal challenges defined at grand scale. Decentralisation of digital infrastructures that increasingly govern our societies could be such a mission.

Decentralising our technological infrastructure must aim at increasing Europe's technological sovereignty by reducing dependency on non-European technology providers, and to enable fair competition and ensure accountability of service providers. It must also take into account democratic traditions and historic diversity. As such it should provide more agency to European cities - cooperating in the municipalist movement - that are looking for ways to develop decentralised solutions that gain from the relative power and independence of cities as actors.