Introduction

Interoperability is a technical term that describes different systems' ability to connect and communicate with each other. It is a principle that favors open rather than closed communication between systems, based on shared standards. This fundamental but also obscure technical concept and a foundational principle for the internet has recently become a core concept for many proposals to fix the internet.

Interoperability is a principle hidden within many of today's established communication systems, such as telephone services or email. It's also a fundamental principle of the internet and the World Wide Web. It is credited as being essential to the ability of these technologies to be generative: to support innovation and broadly understood value creation. It has been a non-controversial concept for a long time, considered mainly by engineers defining technical rules of interoperability. Urs Gasser describes it as "central, and yet often invisible, to many parts of a highly interconnected modern society."

Interoperability has been proposed as a regulatory principle for each new generation of technologies. In 2015, Urs Gasser argued for interoperability in the context of the Internet of Things. More recently, in 2019, Chris Marsden and Rob Nicholls made the same argument about AI. Today, interoperability is increasingly seen as a regulatory tool to fight market dominance of the biggest online platforms.

At the same time, the online ecosystem has changed significantly over the last decade. One of the critical impact factors has been the growing dominance of a small set of commercial platforms over this ecosystem. As this happens, open communication - based on standards shared between different services - is replaced by closed communication, occurring within a single service and defined by a single commercial actor.

It should be noted that interoperability is not a matter of "all or nothing." There are varying degrees of interoperability that can be applied. The extent of interoperability policies should depend on an analysis of the system to which it is being applied and policy goals that are meant to be achieved. It is a matter of defining both what and how becomes interoperable.

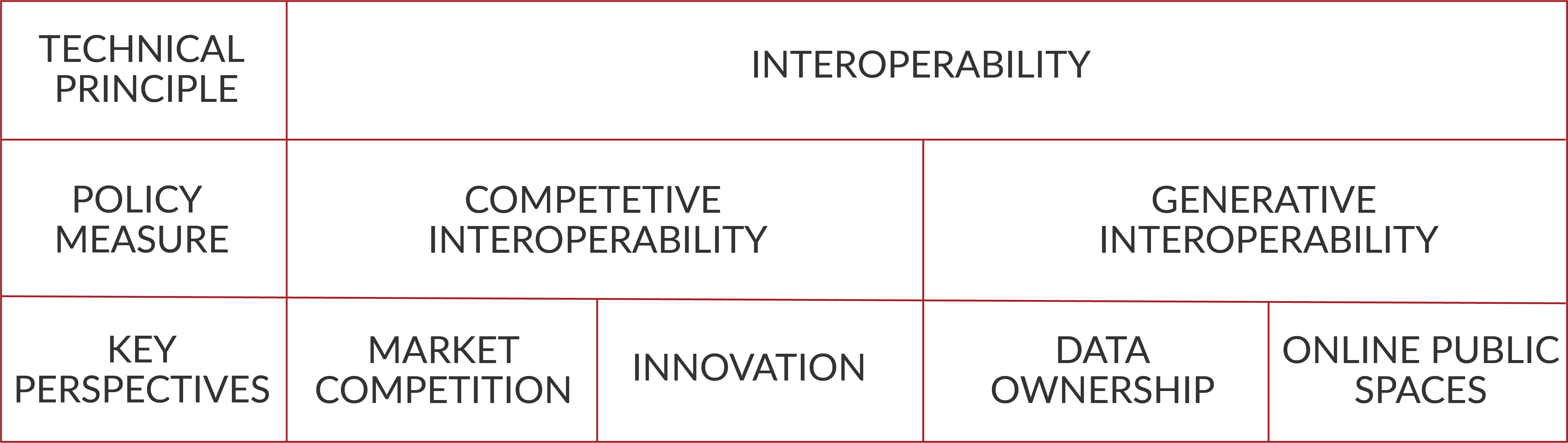

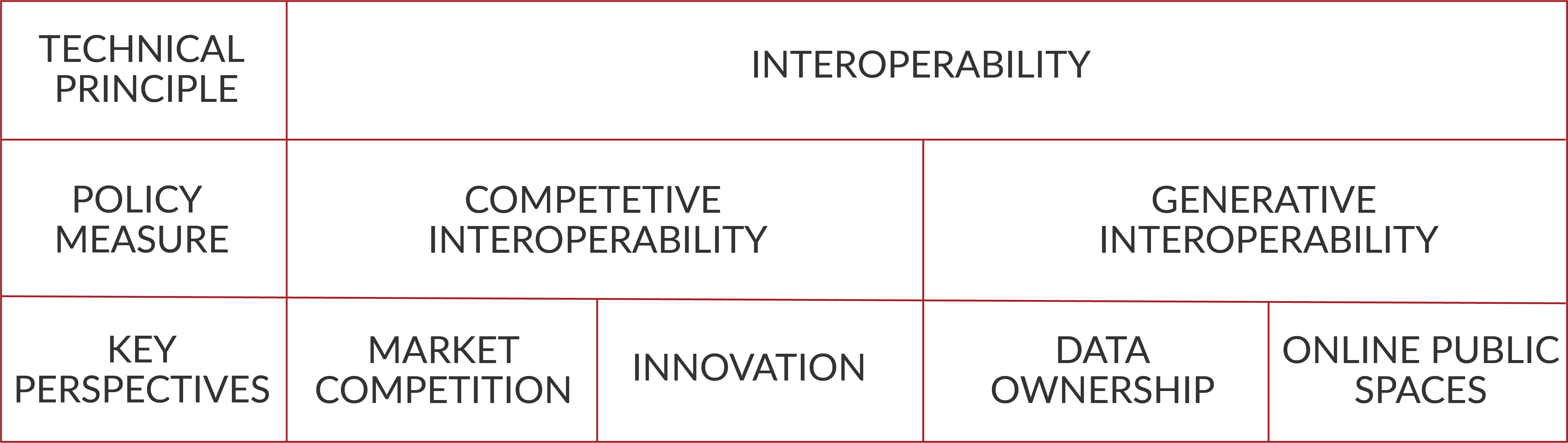

In this document, we present a framework for thinking about two approaches to interoperability, which we call competitive interoperability and generative interoperability. We explain the foundational character of interoperability as a technical concept and trace the origins of these two approaches, tied to four key perspectives on interoperability: competition, innovation, public sphere, and data ownership. Finally, we present an overview of the benefits and costs associated with implementing this principle. We end by suggesting how the two approaches fit into Europe's current digital policies and propose our vision of an Interoperable Public Civic Ecosystem.

Competitive and generative interoperability

In the literature and expert debates on interoperability, two different visions and approaches to interoperability can be identified. In these two approaches, the same term - and the same technical principle - forms the basis for two very different policy approaches. We will call one of these approaches competitive interoperability and the other generative interoperability. In the next part, we will further describe essential perspectives on interoperability that align with one of the two approaches.

In today's policy debates, interoperability is often mentioned as a corrective measure for the deficiencies and pathologies related to the dominant online platforms and their influence on the online ecosystem. For example, it is an important mechanism in the European Commission's Digital Services Act. It is listed as a key regulatory measure in the report on "Online platforms and digital advertising", published in July 2020 by UK's Competition & Markets Authority, as well as the "Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets" by the Judiciary Committee of the United States Congress. We will call this approach competitive interoperability , as it is strongly connected with a perspective focused on market competition. In this approach, the interoperability principle is translated into regulation that fixes markets.

Competitive interoperability is one of the regulatory options on the table in debates about regulating the dominant internet platforms. It's proponents argue that the alternative approach - focused on regulating the behavior of the existing platforms without attempting to reshape the ecosystem in which they function - has the adverse effect of giving these commercial players even more power. In this approach, interoperability is the tool that forces open the "walled gardens" of today's online platforms. It introduces market competition and, as a result, "fix[es] the Internet by making Big Tech less central to its future".

An alternative approach - which we call generative interoperability - sees it mainly as a positive principle. One that does not provide a fix, but establishes a positive norm. In this approach, the interoperability principle becomes foundational for an open online ecosystem (not necessarily a market). The concept of generativity, as proposed by Jonathan Zittrain, defines systems that "produce unanticipated change through unfiltered contributions from broad and varied audiences" by providing leverage, being adaptable, easy to access and master, and to transfer changes to others.

There is a growing body of policy visions that sees the online ecosystem from this perspective. In 2019, we presented our report "A Vision for Shared Digital Europe", where we argue that Europe needs to create a digital space that enables self-determination, cultivates the commons, empowers public institutions, and is built on decentralized infrastructure. In order for this to occur, European digital policies need to shift from a market focus - to a vision of a digital society or digital public sphere that is built with internet technologies. From this perspective, an ecosystem that meets a technical standard of interoperability is one that also meets the societal values represented by the concept of the public sphere. A recent report titled "European Public Sphere. Towards Digital Sovereignty for Europe", published by the German National Academy of Science and Engineering (acatech) offers a good formulation of this perspective, albeit interoperability is mentioned in this report only briefly. A similar perspective is presented in "A Vision for the Future Internet", a working paper recently published by NGI Forward, which argues for a "more democratic, resilient, sustainable, trustworthy and inclusive internet by 2030".

The origins of generative interoperability

Looking back, the World Wide Web can be seen as a template for a system based on the principle of generative interoperability. Tim Berners-Lee's original idea was essentially that of a set of tools enabling information to flow freely between computers and servers, regardless of the technological stack used in a given instance. This principle was initially applied within CERN, the research institution where Berners-Lee was based. Soon afterward, it defined the World Wide Web. It was not used to "break open" any existing communication ecosystem but rather determined the success of a new, alternative ecosystem.

Key factors that enabled the World Wide Web to win over other competing projects were the simplicity of the system and openness of standards, such as the HTTP protocol and HTML markup language. WWW also introduced URI (Universal Resource Identifier), meaning each piece of content received a unique, para-permanent address. These three combined factors were essential for ensuring that the WWW was an interoperable system.

The interoperability debate has gone a long way since the beginning of the World Wide Web. Initially, the idea of interoperability meant the ability of a variety of systems and actors to communicate between themselves (as a result of generative interoperability). It also meant a technological stack, in which interoperability at lower layers enabled services built on top of them to function in an open ecosystem. Today, the most relevant debate concerns interoperability among these new services, built on top of the WWW. Addressing the issue of "online walled gardens" and ways in which they act as new gatekeepers to online communication (through competitive interoperability) is crucial for further development of this ecosystem. At the same time, several reports have recently addressed anew the significance of public digital infrastructures, including Ethan Zuckerman's "The Case for Public Infratructure" and Waag's Public Stack project. An infrastructural perspective, addressing varied layers of the technological stack of the internet is also prominent in the NGI Forward working paper "A Vision for the Future Internet".

Ultimately, the two approaches should be seen as complementary, despite having divergent goals and theories of change behind them. Both of them ultimately refer to the interoperable character of the early internet and the early Web, which has been largely lost today. "We need to take inspiration from what the Internet's early days looked like", declares the Electronic Frontier Foundation . The first one aims to break the dominance of commercial platforms, which have destroyed the decentralised character of the internet and contribute to a range of problematic societal developments. The latter focuses on securing a public interest-driven ecosystem in those spaces, where these actors are not yet dominant. This second strategy has been elegantly expressed by Ursula van der Leyen in her political guidelines for the European Commission: "It may be too late to replicate hyperscalers, but it is not too late to achieve technological sovereignty in some critical technology areas".

Definitions of interoperability

Interoperability is the ability of different systems to connect and communicate with each other. Urs Gasser defines interoperability as "the ability to transfer and render useful data and other information across systems, applications, or components". The Electronic Frontier Foundation defines it as "the extent to which one platform's infrastructure can work with others". Gasser notes that a more precise, one-size-fits-all definition is not possible. The extent and characteristics of interoperability depend on context and perspective. In order to acknowledge this, Gasser distinguishes four layers of interoperability: technological, data, human, institutional.

For many people, it is the exchange of data through technological means that comes to mind when they think about interop. But it turns out that the human and institutional aspects of interoperability are often just as – and sometimes even more – important than the technological aspects.

The technological layer described by Gasser consists primarily of the hardware and code underlying interoperable systems. The data layer is key for technological systems to understand each other and is built by the Linked Data and Semantic Web standards and ontologies. The human layer, in turn, is the one where the ability to understand and act on the data exchanged (e.g., common language) is situated. Finally, the institutional level focuses on the societal system's ability to engage with an interoperable system (e.g., demanding shared laws, understanding of regulation; does not demand complete homogeneity of legal systems, however).

As an example, he describes mobile payment systems. On a technological level, it is built by banks, devices, and payment platforms. On a data level, it is about the protocols enabling transaction processing, NFC-ability of cards, and readers. For humans, it is a simple and understandable system with a close resemblance to plastic card transactions.

In the case of the internet, the principle of interoperability is brought to life in different ways across the different layers of its technological stack, running from the physical infrastructure, through the protocol layer, to applications, data and content flows, and finally the social layer at the very top.

Another useful conceptualization of interoperability and related concepts comes from a recent report for the European Commission. Jacque Crémer, Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, and Heike Schweitzer distinguish between four related concepts that define increasingly strong forms of interoperability . First, they define data portability. It is "the ability of the data subject or machine user to port his or her data from service A to service B". In Europe, the right to data portability is provided by Article 20 of the GDPR. Crucially, data portability does not mean real-time access to data.

Afterward, they distinguish between protocol interoperability and data interoperability. The first term, protocol interoperability , defines a more traditional understanding of interoperability as enabling two services to interconnect. These services are typically complimentary but cannot substitute for each other. One example is a service operating on top of a platform that enables its functioning (e.g., case of Microsoft's operating system enabling programmes to operate). Crucially, this type of interoperability does not require the transfer of data or does so in a limited manner. Data interoperability , in turn, is defined as "real-time, potentially standardised, access for both the data subject/machine user and entities acting on his or her behalf". This type of interoperability allows not only complementary services but also the substitution of functionalities of one service by the other. Finally, full protocol interoperability requires two substitute services to interoperate fully. This is the case with mobile phone networks, emails, or file formats. The authors order these different types of broadly understood interoperability according to their strength as a regulatory mechanism, from data portability to full protocol interoperability.

To conclude, the principle of interoperability contains a technological aspect (protocols, technical requirements), has specific data requirements (formats, syntax, semantics), but crucially also has human and institutional dimensions. This institutional dimension includes the economic dimension of interoperability, as business models are a key factor that determines whether a given part of the online ecosystem is interoperable or not. Furthermore, interoperability mandates can differ in their strength as a regulatory mechanism, and therefore also have a differing impact. Finally, key questions concern the type of broadly understood resources that are made interoperable.

Key perspectives on interoperability

Interoperability is ultimately a simple, foundational principle for online communications. Below we present four key policy perspectives on interoperability, focusing on market competition, innovation, online public spaces, and data ownership. For each of them, the same technical principle becomes a means for achieving different goals. These four perspectives do not fully align with the two approaches that we defined previously. Although a market competition perspective is key for competitive interoperability and a public space perspective defines generative interoperability.

Interoperability and market competition

Arguments in favor of introducing greater interoperability of modern communication systems, and in particular of dominant online platforms, are most commonly framed in terms of market competition.

In 2002, Viktor Meyer-Schöneberg brought attention to the issue of interoperable public service networks used in emergencies. In his paper "Emergency communications: the quest for interoperability in the US and Europe", he described the three key characteristics of a technological solution allowing for interoperability between a variety of actors:

- suitable technology (one that scales and accommodates many users simultaneously),

- common standards (including protocols and procedures), and

- funding that sustainably supports necessary infrastructure.

By comparing the EU TETRA network for public services with similar US projects, he highlighted the need for an uncomplicated set of common communication standards. He also praised the European approach for using public-private partnerships to develop the system.

In 2018, Viktor Meyer-Schönberg and Thomas Ramge proposed a "progressive data sharing mandate", based on modeling of data-driven markets, conducted by Jens Prüfer and Christoph Schottmüller. The mandate would force dominant actors in a market to share a portion of collected data with their competition. The amount shared would be proportional to the company's market share.

Interoperability and innovation

Innovation is typically mentioned, alongside market competition, as a key positive outcome of greater interoperability. In a recent interview with MIT Tech Review, Viktor Meyer-Schönberg stated:

Innovation is moving at least partially away from human ingenuity toward data-driven machine learning. Those with access to the most data are going to be the most innovative, and because of feedback loops, they are becoming bigger and bigger, undermining competitiveness and innovation. So if we force those that have very large amounts of data to share parts of that data with others, we can reintroduce competitiveness and spread innovation. (...) You can break up a big company, but that does not address the root cause of concentration unless you change the underlying dynamic of data-driven innovation.

Interoperability has been studied by researchers from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, especially in the context of driving innovation. In 2005, Urs Gasser and John Palfrey published a report, where they conclude that ICT interoperability needs to be defined within specified context, subject, and topic. In their work, they analyse three case studies (of DRM-protected music, Digital ID, and Mashups) indicating different levels of interoperability. They also list available methods to build interoperable ecosystems, both from the state and from the private sector side. Finally, they conclude that indeed ICT Interoperability should be beneficial for innovation, but "the picture is filled with nuance". They further developed the ideas in the 2012 book "Interoperability: The Promise and Perils of Highly Interconnected Systems".

Interoperability as a foundational principle for online public spaces

There is a long history of defining the internet as a public space, going back to John Perry Barlow's "A Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace". Peter Dahlgreen already in 2006 described the internet as a basis for some of the democracy's communication spaces (an idea taken from Habermas) in an article "The Internet, Public Spheres, and Political Communication: Dispersion and Deliberation". On the one hand, he appreciated many of the characteristics of the online spaces (e.g., the ability of the audience to interact), but also warned against the drawbacks we observed a few years later (the blurring of journalism with non-journalism, disengagement of citizens, business models focused on short-term profits). His idea was to create "domains" (not in the technical sense of an internet domain, but a more general political understanding of a space or platform) for public advocacy and activists, journalism, politics and supplement them with civic forums. The paper describes a general idea, but it lacks any description of the implementation.

A case for interoperability has been proposed by Jonathan Zittrain, who defined for this purpose "generative" systems. Generativeness of a system is defined as an ability to create new systems and innovate; generative technologies are defined as ones having the capacity for leverage (becoming useful for services built on top of them), adaptability, ease of mastery, and accessibility. Zittrain argues that the original Web was a prime example of a generative system, but it loses this trait as the Web matures and becomes more stable. Hence, he argues, the interoperable and open nature of PC computers, networks, and "endpoints" (services built on top of the Web; today, we should include platforms in this category) is crucial for further development.

Another insightful and more recent paper comes from legal studies. In "Regulating informational infrastructure: Internet platforms as the new public Utilities" K. Sabeel Rahman aims to set the main routes of regulation of online public spaces. He describes the goals of such regulation:

- fair access and treatment (non-discrimination, neutrality, common carriage, fair pricing, non-extractive terms of service),

- protection of users (e.g., fiduciary duties with respect to user's data, protection against algorithmic nuisance)

- accountability of platforms.

Then proceeds to describe three main approaches: managerial, self-governing managerial, structuralist. The managerial approach focuses on regulatory oversight, implementation of a variety of forms such as algorithmic impact statements, which would require new statutory authorities or regulatory bodies. The self-governing managerial approach highlights the responsibility of the private sector by being oriented toward guarding public responsibility, standards, and accountability. Structuralist regulation, according to Rahman, would focus on limiting the business models of firms, altering the dynamics of the market, e.g., by renewed antitrust regulation, creating a tax on data use, or creation of "public options" as alternatives to a private stack (or endorsement of "vanilla" options of privately operated services that are publicly available). This option is viewed as incurring lower costs but should not be viewed as cost-free.

Interoperability and data governance

The fourth perspective focuses on the fact that interoperability enables content and – in particular – data flows. Managing these data flows is, therefore, a key challenge for interoperable systems. This perspective focuses, therefore, on data governance, often framed in terms of data ownership.

The importance of data ownership as means of enabling societally beneficial use of data and of protecting at the same time privacy was signaled in 2009 by Alex Pentland, who proposed a "New Deal on Data". Pentland argued that the basic tenets of ownership - right to possess, use, and dispose of - should apply to personal data. He also argued that policies need to encourage the sharing of data for the common good. While interoperability is not mentioned by him explicitly, it is clear that his proposal assumes data interoperability.

In 2012, Doc Searls proposed in his book "The intention economy" a VRM (Vendor Relationship Management, a twist on the CRM - Customer Relationship Management) system that addressed tensions between data ownership and privacy protection. He described VRM as a personal data hosting service for individuals, hosting information about him/her and allowing the user to set Terms and Conditions on how they may be accessed by external services (e.g., platforms).

Searl's idea did not directly translate into a technological solution, but it inspired the work of others. SOLID, Tim Berners-Lee's current project is a personal data hosting solution that will enable the creation of decentralised services and applications, which use data in ways that are fully under users' control.

One other prominent approach is being developed by MyData, which envisions - in the MyData Declaration - an ecosystem in which trusted intermediaries manage users' personal, with the goal to empower individuals with their personal data, thus helping them and their communities develop knowledge, make informed decisions, and interact more consciously and efficiently with each other as well as with organisations.

One of the key debates on data governance concerns the idea of data as an asset that can be owned - especially personal data. Luigi Zingales and Guy Rolnick, in an op-ed in the New York Times, proposed personal data ownership and interoperability as solutions to the challenges of the modern Web (of personal data, but also of data generated by platforms using personal data). In an influential article titled "Should We Treat Data as Labor?", a group of researchers tied to the RadicalxChange initiative suggest a "Data as Labor" approach that sees data as "user possessions that should primarily benefit their owners". There is also growing literature on ways of collectively managing data for the public good. For example, Mariana Mazzucato proposed, in her op-ed "Let's make private data into a public good", a public repository that "owns public's data and sells it to the tech giants". The idea of data ownership is opposed by an approach based on the idea of data rights, presented clearly by Valentina Pavel in "Our Data future".

Benefits and costs of interoperability

Interoperability is a structural principle and not a goal in itself. It is rather a means for attaining other policy goals. At the same time, by virtue of its generative nature, it is a simple principle that creates open systems with complex outcomes.

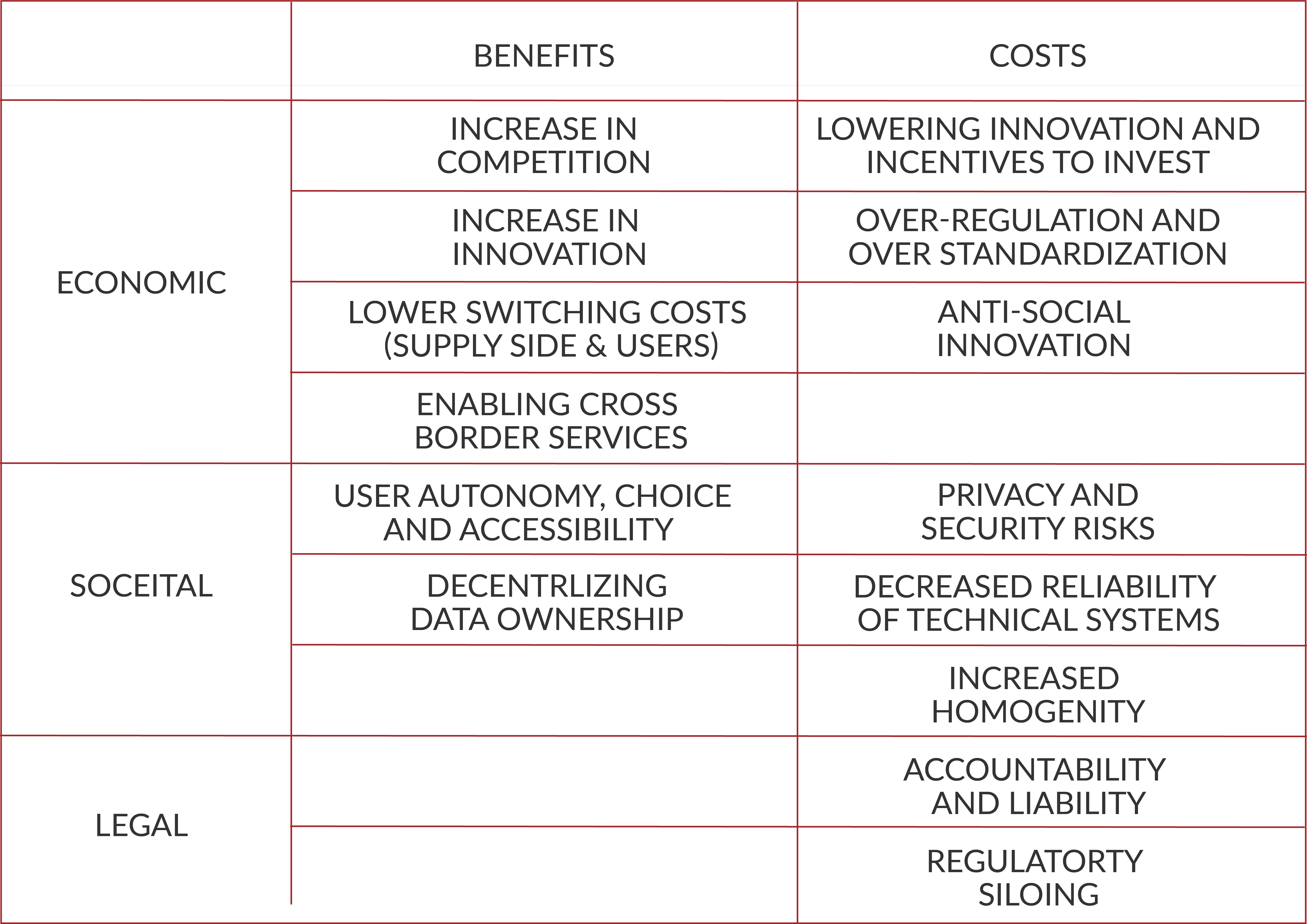

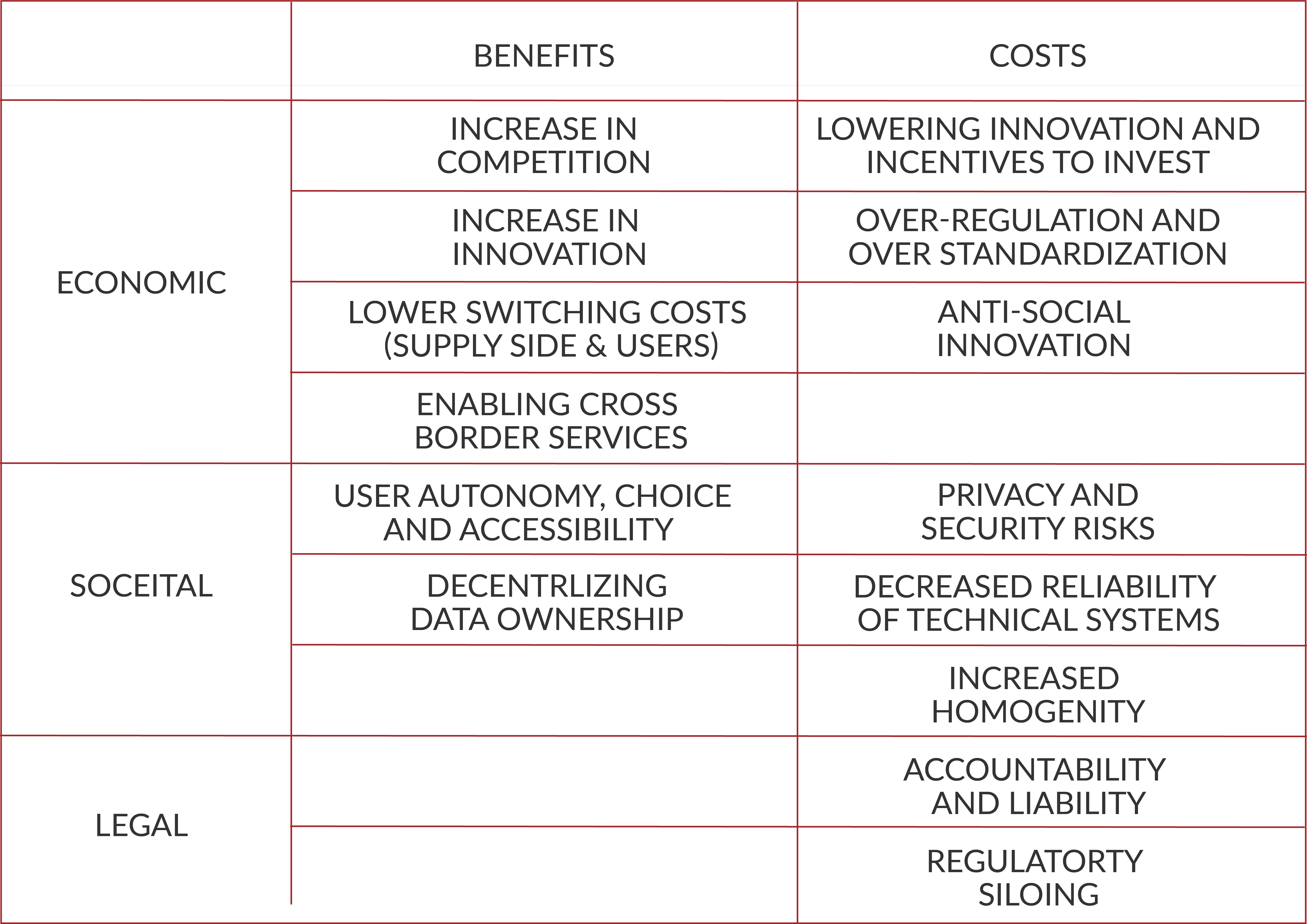

Most commonly, interoperability is seen as a tool for increasing competition and innovation. Yet, our literature review shows a broad range of effects that the introduction of a principle of interoperability can have. Below you will find a summary of the arguments for introducing interoperability, followed by arguments against it and its adverse effects. We have divided the arguments into economic, societal, and legal ones.

In policy debates on interoperability, proposals are often made on the basis of faith in principles and not on the basis of evidence - which, admittedly, is usually not available. For example, in the case of dominant online platforms, there is a persistent lack of data that makes it challenging to model the effects of any changes in how data flows are controlled. It is similarly hard to model in detail the effect that decentralised, interoperable alternatives would have on different aspects and actors in the online ecosystem.

Nevertheless, based on our literature review, we believe that it is not enough to have faith in interoperability as such or to refer to past examples - as these relate to different, much simpler technologies and media ecosystems - favorite examples of interoperability researchers concern text messages and emails, while our concern today are services that manage multiple flows and layers of content and data, often with the use of opaque algorithms.

Economic benefits

Increasing competition (& de-monopolising the Web)

In the world of protocols, you still get the global connectivity benefit, but without the lockdown control and silos (and, potentially, the questionable privacy practices). In a world of protocols, there may be a global network, but you get competition at every other level. You can have competitive servers, competitive apps and user interfaces, competitive filters, competitive business models, and competitive forms of data management.

Urs Gasser argues that internet interoperability is a tool helping economic innovation as it lowers the lock-in effects and hence decreases the entry barriers to certain industries. He gives an example of HBO content distribution, which used to be confined to cable and satellite providers; by extending its availability to web browsers and TV-enhancing devices (Chromecast, PlayStation, Roku), it has increased competition for subscription TV services. Operators of cable, satellite, and online TV subscription services can no longer rely on user lock-in (meaning the inability to access the content elsewhere).

Gasser also discusses two counter-arguments. Firstly, in some circumstances, interoperability could lead to a lack of competition. For example, bilateral agreements or closed standards - even when they enable interoperability - can, over time, prove to be anticompetitive. Interoperability can be deployed as a tool for building closed ecosystems.

Secondly, he argues that reaching maximum competitiveness does not imply maximum innovativeness. A different model of innovation assumes that monopolists also have incentives to innovate, and competition functions through "leapfrogging" - replacing incumbent players by designing a new generation of technology that grants temporary dominance.

Crémer et al. in a report for the European Commission state:

access to a large amount of individual-level data have become key determining factors for innovation and competition in an increasing number of sectors. We will discuss access to individual-level data by platform and within ecosystems later in this chapter, and at some length in the data chapter, including questions of data portability and data interoperability for personal and machine individual-level data, questions of access to privileged and private APIs, and the self-reinforcing role of data in ecosystems and leveraging market power.

Increasing innovation

Interoperability is often portrayed as a tool enabling the emergence of new services built on top of pre-existing infrastructure and other services, hence igniting innovation. An argument of such kind is proposed by Urs Gasser. He also refers to the early times of the WWW as an example of innovation-incurring interoperable systems. He also cites IoT interoperability as a modern example of a platform that has the potential to inspire the creation of new services.

Interoperable ecosystems can also be viewed as ones fostering science and research activities, as was highlighted by the European Commission's Staff Working Document, "A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe –Analysis and Evidence":

[In Europe] neither the scientific community nor industry can systematically access and re-use the research data that is generated by public budgets, despite strong demand.

Crémer et al. state in their report:

the entry of new competitors might be facilitated by multi-homing and interoperability. If users can use several platforms at the same time, i.e., multi-home, it will be easier for a new entrant to convince some users to switch to their platform while still being able to conserve the benefits of using the incumbent platform to interact with others.

Lower switching costs on the user- and supply-side

Ben Thompson expands on the hypothesis that interoperability (especially via API disclosure) could help defuse the market power of aggregators. His "Aggregation Theory" describes the unique position of online aggregators (which include many online platforms), who work with near-zero distribution and transaction costs and rely on a superior customer experience, leading to a network effect promoting these already large services.

According to Thompson, once an aggregator gains a monopolistic position, it becomes a monopsony: also the only buyer for specialized suppliers:

And this, by extension, turns the virtuous cycle on its head: instead of more consumers leading to more suppliers, a dominant hold over suppliers means that consumers can never leave, rendering a superior user experience less important than a monopoly that looks an awful lot like the ones our antitrust laws were designed to eliminate.

He argues that mandated API disclosure and interoperability (a solution imposed on e.g., Microsoft) can address this issue, as these measures decrease the switching cost for the consumer. For example, the switching costs in the case of Uber remain relatively low despite its large user pool exactly because it does not benefit from a monopolistic position with relation to customers or drivers, both of whom can easily switch platforms or multi-home: use multiple platforms simultaneously. Mandated API and interoperability could lead to a similar effect in cases where network relationships play a crucial role. He also highlights that interoperability could be beneficial on the supply side as well. For example, not just passengers but also drivers would be able to export data from Uber to a competing platform.

Thompson finalizes his argument by saying that technologies with fixed costs that rely on network effects generate innovation, as there are enough potential rewards by simply being first. He argues there is no need for strict preservation of intellectual property.

Cross-border public services

In the European context, the principle of interoperability can support the cross-border character of online services in the Digital Single Market. The European Commission, in the Staff Working Document, A Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe –Analysis, and Evidence, highlights that interoperable online services are a tool for enabling cross-border public services to work, an issue especially important in the European context. This notion can be extended to cross border delivery of goods and services in general.

More generally, the lack of interoperability among public entities and private operators restricts the potential for digital end-to-end services, One Stop Shops, the once-only principle, the single data entry principle, the transparency of public services, and the full exploitation of public open data. [...] 25% of firms in the EU state that interoperability issues are a problem for cross-border online sales, with 10% declaring it to be a major problem.

Societal benefits

User autonomy, choice, and accessibility

Effective interoperability gives users the ability to choose and move from one service to another effortlessly. Current strong lock-in effects have not been lowered adequately by the GDPR. "Voting with one's feet" is an essential element of a free-market economy, but its importance extends beyond the economy itself, as it enables one to stand guard for civil rights and liberties (e.g., in the case of changing Terms and Conditions limiting privacy rights).

Single sign-in digital ID infrastructure (possible today with Facebook and Google login) is also an example of how interoperability enables access and openness for users, notes Urs Gasser.

Marsden and Nicholls write in "Interoperability: A solution to regulating AI and social media platforms":

There are social benefits of interoperability. It eliminates the consumer need to acquire access to every network or the tendency to a winner-takes-all outcome. This is inelegant from a device design perspective, too: readers may remember when the US had different mobile design standards to the EU (CDMA rather than GSM). In Instant Messaging (IM), arguably the winner-takes-all is Facebook/WhatsApp/Instagram without interoperability – with all IMs inside the corporation becoming interoperable.

De-centralising data ownership

Gus Rossi and Charlotte Slaiman develop an argument that interoperability could foster new players and actors to develop data banks. They claim that the current centralization of data ownership in a handful of companies translates into their superior position in AI development. This, in turn, can further lead to novel approaches towards data storage and ownership and possibly a wider variety of services focused on privacy.

To conclude, proponents of interoperability highlight its ability to address the issues with a lack of competition in many of the online spaces, increasing the choice of individuals using online services (especially regarding data privacy) and their control over data.

Economic costs

Lowering innovation and incentives to invest

Thomas Lenard criticizes interoperability as a potential solution to the challenges of the Web as, in his view, it will decrease innovation on the internet. His reasoning is based on an extended understanding of data portability (or "interoperability of data"; term to include also the data inferred about a user and/or his social graph). He argues that greater interoperability would reduce the rents collected by innovators. As the (costly) new features and results of work of algorithms available on their services will become available via API (or will be easily copied), services built alongside or on top of platforms may easily catch-up and draw clients to themselves.

He argues that "winner-takes all" markets (such as the ones we observe on the Web) are always risky investments because of the unpredictability of the outcome. Making it easier for the competition to catch-up and for users to switch for investors would translate into a possibly shorter time to retrieve profits from innovation, hence discouraging them from investing in the first place.

Over-regulation and over-standardising

Thomas Lenard in his paper also considers how mandating interoperability (e.g., via the ACCESS legislation, "Augmenting Compatibility and Competition by Enabling Service Switching Act of 2019" in the US) would effectively favour the existing large platforms, who have the resources to adjust to the regulation, become the first to use newly available data from the competition and have the market position enabling them to survive. The cost-side of the interoperability proposals would however similarly affect firms of all sizes, creating the need for adjustment for big companies and startups.

In fact, some of the internet platforms are cooperating on a form of interoperability in the Data Transfer Project, which will be mentioned in the second part of the essay.

Anti-social innovation

Urs Gasser mentions that although innovation - often seen as one of the key outcomes of interoperability - is usually viewed in a positive context, it is a double-edged sword:

Innovation can be bi-directional. Just as interop can help support the development of innovative devices and software that has positive social value, it can also support innovative devices and software with negative social value. On the internet, worms, viruses, spam, and other unwanted activity are in many ways just as "innovative" and just as dependent on interoperability as more positive developments.

Gasser gives the example of the Heartbleed vulnerability in the SSL protocol that enables secure, encrypted communication across the internet - and due to the vulnerability, in fact, compromised communication. But potential hazards are not limited to hacking of the technological stack but include as well disinformation or novel methods of election manipulation.

It is worth noting that for some, this aspect is, if not a benefit, then at least a neutral and necessary part of interoperability. Cory Doctorow argues that "It's possible that people will connect tools to their Big Tech accounts that do ill-advised things they come to regret. That's kind of the point, really".

The advantages tied to the freedom of making own uses of tools exceed the possible costs. Especially if the alternative is giving dominant market players the right to decide, which uses and innovations are beneficial, and which ones are not.

Societal costs

Privacy & security risks

Security and privacy are one of the primary concerns regarding interoperability.

Ben Thompson in "Portability and interoperability" describes the history behind Zuckerberg's 2019 declaration to support interoperability. He highlights that the declaration and indeed the activities in the Data Transfer Project (of which Facebook is a founding member) initiative do not go as far as to include interoperability of what Thompson argues is the valuable data - e.g. information about user's network of friends (also referred to as a "network transfer tool"). Facebook initially supported an API enabling other entities to see user's friends (which was called an Open Graph). Over-exploitation of this API has, however, resulted in the Cambridge Analytica scandal and led Facebook to a decision to close the API.

Furthermore, even before the scandal Facebook has limited access to the API for services aiming to "replicate our functionality or bootstrap their growth", indicating that the company has become afraid of a scenario where their costly investments are being easily duplicated or used by other entities. Such an argument was described above, in the part that concerns lowering innovation and investment incentives.

Decreased reliability of technological systems

The complexity of the increasingly standardized system creates fragility, as there is a chance some flaws will propagate worldwide – as in the case of flaws in the SSL protocol. People and companies will increasingly depend on standards without having the means to fix them (as they normally would with simpler architectures).

Urs Gasser extends this argument with an example of not only security risks but also business reliance:

As interoperability increases, downstream systems may become increasingly reliant on upstream systems. This problem was observed when Twitter's decision to change its open API threatened the business of the downstream systems that were built on top of that API.

Hence, businesses relying on others can have limited control over the fundamental elements of their model. Urs Gasser provides an example of a Kindle lock-in mechanism (using proprietary .mobi format for e-books), which he argues enables Amazon to almost arbitrarily lower prices.

Increased homogeneity

Similar network effects to those driving the dominant platforms of today can make a very narrow set of interoperability standards dominant. This is not bad per se, as homogeneity has a positive side (e.g., enabling scaling for small companies), but it can also limit innovation:

Internet is a wonderfully interoperable system that has led to tremendous innovation, the protocols that underlie it represent a form of homogeneity. Most of the interconnected systems that people use today rely on TCP/IP. In the same way, email protocols have become a de facto standard, meaning that innovations in security for email must be built upon an existing set of protocols.

Legal costs

Accountability and liability

The increasing complexity of systems also needs consideration regarding blurring boundaries of responsibility (it has to be noted that a similar debate takes place on the topic of automated decision-making systems). This issue is highlighted by the PrivacyTech whitepaper, published as part of the A New Governance initiative:

Legal aspects of data circulation and portability are not cleared by GDPR entirely. Many companies are still not comfortable with the idea of data circulation. They fear liability issues if they open up their data to other organizations. Data circulation has also become a media issue since Facebook's Cambridge Analytica scandal. Many corporates fear negative press coverage that would result from a misuse of data circulation. We need to define a liability model for data circulation that would be based on GDPR and would reassure all the stakeholders of the ecosystem. For it to be accessible to any company, whatever its resources, it has to be defined as a standard monitored through proper governance.

The proposed Data Governance Act presented by the European Commission aims to address some of these questions by introducing a "supervisory framework for the provision of data sharing services".

Regulatory siloing

Although it is probably more a challenge than a drawback of interoperability, it is worth mentioning the argument raised by the A New Governance initiative:

The energy and the will to build new standards is already there. Many domains and expertise are involved: legal, technical, design, business, policy. Many sectors are involved: Mobility, Healthcare, Administration, Commerce, Finance and insurance, Entertainment, Energy, Telecom, Job market, Education, etc. The main problem is that all those initiatives are partial as they mostly work by country, by sector, by expertise or through closed consortia. Despite our energy and good will, we are recreating silos, which will be highly detrimental to the main goal. Personal data circulation and protection is a cross-sector issue, and data have no boundaries.

A more complex picture is also presented in "Data sharing and interoperability: Fostering innovation and competition through APIs" by Oscar Borgogno and Giuseppe Colangelo:

Analysing the main European regulatory initiatives which have so far surfaced in the realm of data governance (right to personal data portability, free flow of non-personal data, access to customer account data rule, re-use of government data), it seems that the EU legislator is not tackling the matter consistently. Indeed, on one side, all these initiatives share a strong reliance on APIs as a key facilitator to ensure a sound and effective data sharing ecosystem. However, on the other side, all these attempts are inherently different in terms of rationale, scope, and implementation. The article stresses that data sharing via APIs requires a complex implementation process and sound standardization initiatives are essential for its success.

Despite the several legislative initiatives put forward so far by the European Commission, a clear view as to who should define APIs and how they should define them is still lacking.

Summarising costs and benefits

As illustrated in the table below, there are widely varying perspectives on the benefits and costs of interoperability - and ultimately on its societal and economic desirability as well.

A substantial amount of these arguments takes "innovation" as a proxy for the desirability of interoperability (and other regulatory interventions). In summarizing the different perspectives, it is important to note that innovation can have both positive and negative effects on society. As a result, judging regulatory interventions based on their expected or presumed impact on innovation will be insufficient if we are trying to understand the impact of such interventions.

In the end, interoperability is a technical principle that remains foundational for the networked information ecosystem. After a long period of centralisation and consolidation of the online ecosystem, interoperability has re-emerged as one of the most promising regulatory tools for shaping this digital space.

The question of how interoperability should be used is a political question. Among (European) policymakers there seems to be a broad consensus that competitive interoperability should be used to ensure more competition and limit the market power of so-called gatekeeper platforms. The real question is if the ambition to "Shape Europe's Digital Future" requires a more ambitious approach that embraces as well the generative potential of interoperability.

Generative and competitive interoperability in European digital policies

The current European Commission has presented a new approach to Europe's digital policymaking in the Communication on Shaping Europe's Digital Future. With this policy document, it expands on the previous Commission's market-centered vision of the Digital Single Market. To give an example of this shift, while a previous data strategy would focus on a "market for data" perspective, the new vision outlined in the "European Strategy for Data" calls for "a European data space based on European rules and values".

The two-pronged approach that we propose by distinguishing competitive and generative interoperability is clearly visible in these two documents. On the one hand, they clearly define the challenge posed by platforms that acquire significant scale, turning them into gatekeepers of the online market - thus, policies (especially new competition rules) are envisaged to ensure that markets continue to be fair and open.

But European policymaking does not stop here. Policies are also being designed not to solve the challenge of the platforms but with the aim of building a trustworthy digital society. In December 2019, European Commission President van der Leyen presented this two-pronged approach by stating that:

It may be too late to replicate hyperscalers, but it is not too late to achieve technological sovereignty in some critical technology areas. To lead the way on next-generation hyperscalers, we will invest in blockchain, high-performance computing, quantum computing, algorithms and tools to allow data sharing and data usage. We will jointly define standards for this new generation of technologies that will become the global norm.

In such a strategy, competitive interoperability should be used to curb the power of hyperscalers and mitigate their negative impact. Generative interoperability is, in turn, a key principle for the jointly defined technological standards that ensure sovereignty.

This argument is also at the core of the European Strategy for Data, presented in February 2020 by Commissioner Breton, which aims to support the emergence, growth, and innovation of European data-driven businesses and other initiatives. The strategy presents the following argument:

Currently, a small number of Big Tech firms hold a large part of the world's data. This could reduce the incentives for data-driven businesses to emerge, grow and innovate in the EU today, but numerous opportunities lie ahead. A large part of the data of the future will come from industrial and professional applications, areas of public interest or internet-of-things applications in everyday life, areas where the EU is strong. Opportunities will also arise from technological change, with new perspectives for European business in areas such as cloud at the edge, from digital solutions for safety critical applications, and also from quantum computing. These trends indicate that the winners of today will not necessarily be the winners of tomorrow.

Once again, we see the two-pronged approach, which on one hand curbs the power of monopolists and, on the other, supports new markets and ecosystems.

As we argue in "Interoperability with a purpose" this presents an obvious opportunity to put the idea of generative interoperability into action and start building a uniquely European digital space built on civic and democratic values:

In our view, the purpose of generative interoperability must be to enable what we call an Interoperable Public Civic Ecosystem. Such an ecosystem would provide an alternative digital public space that is supported by public institutions (public broadcasters, universities and other educational institutions, libraries and other cultural heritage institutions) and civic- and commons-based initiatives. An ecosystem that allows public institutions and civic initiatives to route around the gatekeepers of the commercial internet, without becoming disconnected from their audiences and communities and that allows interaction outside the sphere of digital platform capitalism. (Read the remainder of our call for an Interoperable Public Civici Ecosystem here)